04

Like many of you, we’ve been keeping a close eye on the CH32 family of RISC-V microcontrollers from WCH Electronics. You can get the CH32V003, featuring 2 kB RAM and 16 kB of flash for under fifteen cents, and the higher-end models include impressive features like onboard Ethernet. But while the hardware is definitely interesting, the software side of things has been a little rocky compared to what we’ve come to expect from modern MCUs.

Things should start looking up a bit though with the release of an Arduino core for the CH32 direct from WCH themselves. It’s been tested on Windows, Linux, and Mac, and supports the CH32V00x, CH32V10x, CH32V20x, CH32V30x, and CH32X035 chips. Getting it installed is as easy as adding the URL to the Arduino IDE’s Boards Manager interface, though as the video below shows, running it on Linux does require an extra step or two.

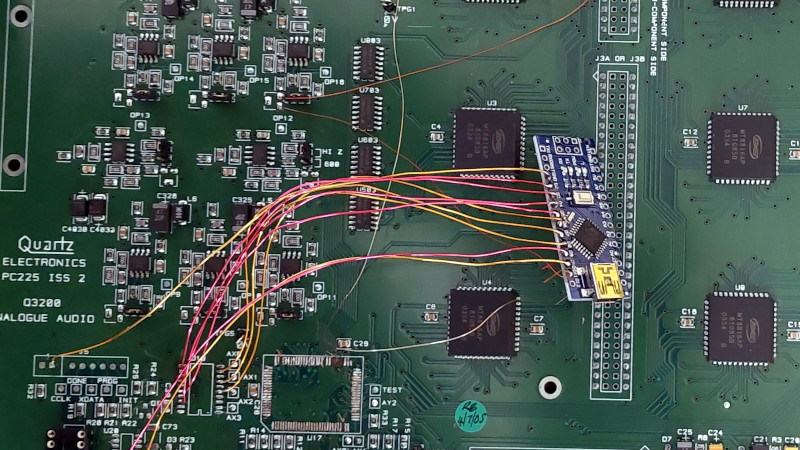

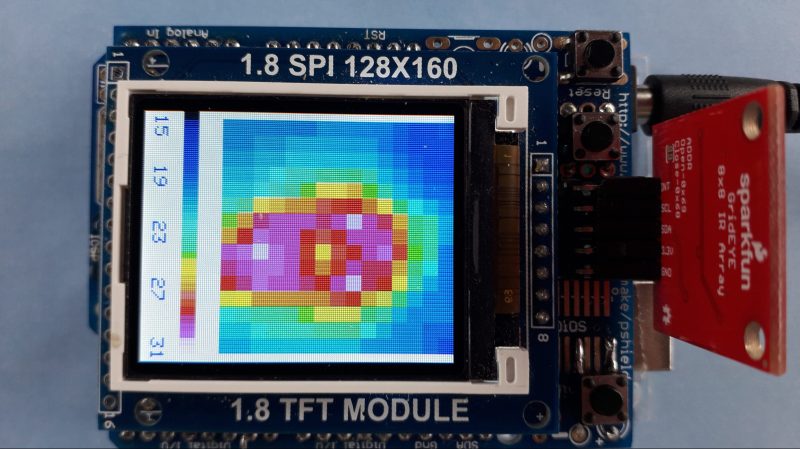

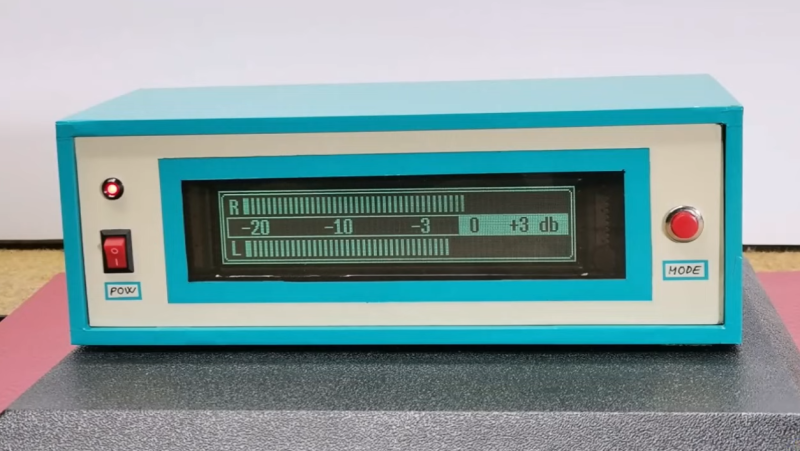

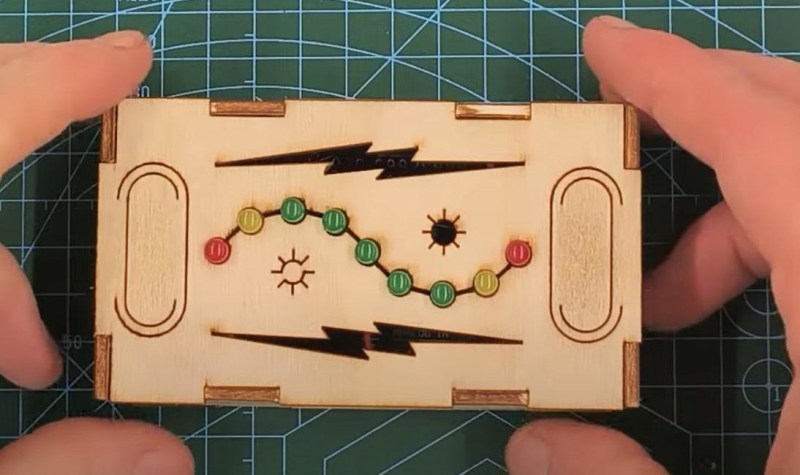

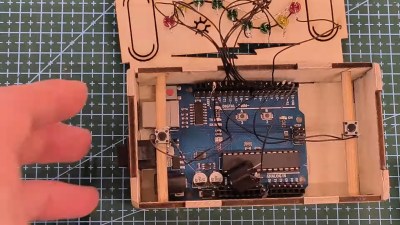

So far, we’ve seen several projects, like this temperature sensor or this holiday gizmo that use [cnlohr]’s open-source toolchain. But there’s no question that plenty of hobbyists out there feel more comfortable in the Arduino environment, and if those folks are now able to pick up a CH32 and do something cool, that means more people jumping on board, more libraries developed, more demo code written…you get the idea.

Just like the ESP8266’s popularity exploded when it was added to the Arduino IDE, we’ve got high hopes for the CH32 family in the coming months.