15

Education – Introduction to Alternating Current – part two

AC, alternating current, CRO, education, electronics tutorial, learning electronics, oscilloscope, phase, phase shift, reactance, resistor, resistor-capacitor, sine wave, tronixstuff, tutorial, voltage divider Comments Off on Education – Introduction to Alternating Current – part two

Hello everyone

Today we are going to continue exploring alternating current, with regards to how resistors and capacitors deal with AC. This chapter is part two, chapter one is here.

To help with the explanations, remember this diagram:

That is, note that there are three possible voltage values, Vpp, Vp and Vrms. Moving on. Alternating current flows through various components just like direct current. Let’s examine some components and see.

First, the resistor. It operates in the same way with AC as it does DC, and the usual calculations apply with regards to Ohm’s law, dividing voltage and so on. However you must keep in mind the type of voltage value. For example, 10Vrms + 20Vpp does NOT equal 30 of anything. But we can work it out. 20Vpp is 10Vp, which is 7.07Vrms… plus 10Vrms = 17.07Vrms. Therefore, 10Vrms + 20Vpp = 17.07Vrms.

Furthermore, when using Ohm’s law, or calculating power, the result of your equation must always reflect the type of voltage used in the calculations. For example:

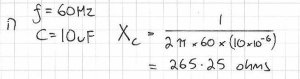

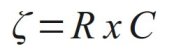

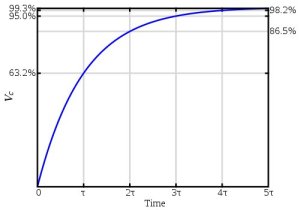

Next, the capacitor. Capacitors oppose the flow of alternating current in an interesting way – in simple terms, the greater the frequency of the current, the less opposition to the current. However, we call this opposition reactance, which is measured in ohms. Here is the formula to calculate reactance:

the result Xc is measured in Ohms, f is frequency is Hertz, and C is capacitance in Farads. Here are two examples – note to convert the value of the capacitor back to Farads

Also consider if you have identical frequencies, a smaller capacitor will offer a higher resistance than a larger capacitor. Why is this so? A smaller capacitor will reach the peak voltages quicker as it charges in less time (as it has less capacitance); wheras a larger capacitor will take longer to charge and reach the peak voltage, therefore slowing down the current flow which in turn offers a higher reactance.

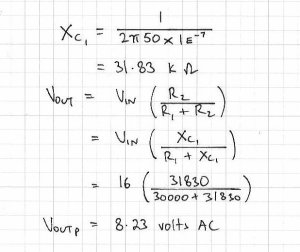

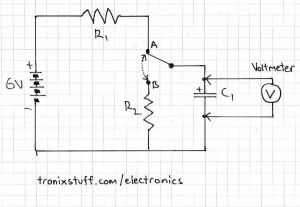

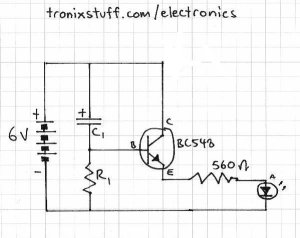

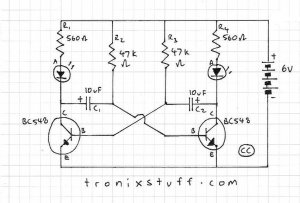

Resistors and capacitors can also work together as an AC voltage divider. Consider the following schematic:

As opposed to a DC voltage divider, R2 has been replaced with C1, the 0.1 uF capacitor. In order to calculate Vout, we will need the reactance of C1 – and subsitute that value for R2:

However, once the voltage has been divided, Vout has been transformed slightly – it is now out of phase. This means that Vout oscillates at the same frequency, but at different time intervals than Vin. The easiest way to visualise this is with an oscilloscope, which you can view below:

Please note that my CRO is not in the best condition. In the clip it was set to a time base of 2 milliseconds/division horizontal and 5 volts/division vertical.

Thus ends chapter two of our introduction to alternating current. I hope you understood and can apply what we have discussed today. As always, thank you for reading and I look forward to your comments and so on. Furthermore, don’t be shy in pointing out errors or places that could use improvement, you can either leave a comment below or email me – john at tronixstuff dot com.

Please subscribe using one of the methods at the top-right of this web page to receive updates on new posts. Or join our Google Group and post your questions there.

Otherwise, have fun, be good to each other – and make something! ![]()