26

Vinduino Water-Smart Farming – Now with LoRa!

2015 Hackaday Prize, 2018 Hackaday Superconference, agriculture, arduino hacks, green hacks, Hackaday Prize, Hackaday Supercon, Hackaday SuperConference, irrigation, irrigation controller, LoRa, soil moisture sensor, The Hackaday Prize, Vinduino, water conservation, water irrigation No comments

Our five rounds of Hackaday Prize 2018 challenges have just wrapped up, and we’re looking forward to see where the chips fall in the final ranking. While we’re waiting for the winners to be announced at Hackaday Superconference, it’s fun to take a look back at one of our past winners. Watch [Reinier van der Lee] give the latest updates on his Vinduino project (video also embedded after the break) to a Hackaday Los Angeles meetup earlier this year.

Vinduino started with [Reinier]’s desire to better understand what happens to irrigation water under the surface, measuring soil moisture at different depths. This knowledge informs more efficient use of irrigation water, as we’ve previously covered in more detail. What [Reinier] has been focused on is improving usability of the system by networking the sensors wirelessly versus having to walk up and physically attach a reader unit.

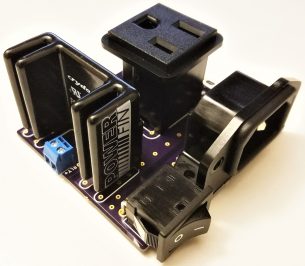

His thought started the same as ours – put them on WiFi! But adding WiFi coverage across his entire vineyard was not going to be cost-effective. After experimenting with various communication schemes, he has settled on LoRa. Designed to trade raw bandwidth for long range with low power requirements, it is a perfect match for a network of soil moisture sensors.

In the video [Reinier] gives an overview of LoRa for those who might be unfamiliar. Followed by results of his experiments integrating LoRa functionality into Vinduino, and ending with a call to action for hackers to help grow the LoRa network. It sounds like he’s become quite the champion for the cause! He’s even giving a hands-on workshop at Supercon where you can build your own LoRa connected sensor. (Get tickets here.)

We’re always happy to see open-source hardware projects like Vinduino succeed, transitioning to a product that solve real world problems. We know there are even more promising ideas out there, which is why Hackaday’s sister company Tindie is funding a Project to Product program to help this year’s winners follow in Vinduino’s footsteps. We look forward to sharing more success stories yet to come.

A flashing LCD screen and a photo-resistor barely make the cut for a one-way LiFi system, but [Eduardo Zola] makes it work. The approach is to build a resitor divider and watch an input pin on the ESP for changes.

A flashing LCD screen and a photo-resistor barely make the cut for a one-way LiFi system, but [Eduardo Zola] makes it work. The approach is to build a resitor divider and watch an input pin on the ESP for changes.